Title page of Yosef Karo's codex, Shulchan Aruch (Set table) with the commentaries by Moses Isserles, Kraków 1594. Yosef Karo (1488-1575), Spanish Jew and Saphed rabbi in Galilee, compiled a code of legal and ritual rules of Sephardic Jews, living in south-western part of Europe. Moses Isserles (ca. 1520-1572), scholar and founder of the Kraków's yeshiva adjusted the code to the customs of the Ashkenazi Jews.

Page no 36 from the charter of the Kraków's kahal, 1595.

The charter consisted in 93 clauses and regulated the activities of the commune: from its internal organization to the private life of its individual members. It became an exemplar for almost all subsequent kahal charters in the Crown and in the Grand Duchy of Lithuania.

Privilege for the Jews issued by Jan III Sobieski in Żółkiew, 1687.

In private towns and cities the legal status of the Jews was determined by the charters issued by the landlords. In most cases those regulations compared favourably with the cities being the royal property, where the municipal authorities strove to restrain the economic activities of the Jews.

|

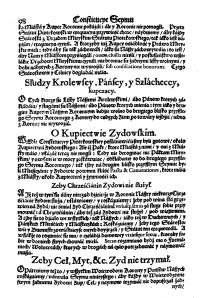

Articles concerning Jews from the Seym constitution, 1565.

The Seym substantially influenced the situation of the Jews in Poland, passing numerous laws that determined the legal framework of their economic activities.

Rabbinical court in Vilnius.

According to the law of the First Republic, legal cases between the Jews were decided by the rabbinical courts. During such cases the Jewish law was in force, including an oath on the Torah. The governor's (voivode) or landlord's court was an appeal instance.

Fragment of the wall-painting from the wooden synagogue in Chodorów, 17th century.

In the territory of Poland there existed at that time numerous wooden synagogues, raised mainly by the poorer communes, that couldn't afford brick or stone building. Nevertheless in many cases they are artistically decorated.

In old Poland there existed several dozen of fortified synagogues, e.g. in Brody, Czortków, Lublin, Łuck, Szydłów, Tarnopol and Żółkiew. They were important for the defense in case of raids of the Tatars or Cossacks. They were also intended as shelters for the Jewish population in case of fire or unrest in the south-eastern borderlands of Poland.

|

Jewish children on their way to heder (jewish elementary school). Painting of Jan Piotr Norblin.

Only boys could attain Jewish schools. Lessons lasted for the whole day, and a teacher (melamed) exacted the learning ruthlessly, from time to time making use of his thin thong. The girls studied at their homes.

The increase of the Jewish population made Polish rulers regulate its legal status. It was done through series of the royal charters and legal or religious restrictions introduced by the Seym of the First Republic and the synods of Catholic Church. By virtue of those legal acts there were established Jewish town districts with independent internal organization, self-government and authorities - kahal. They operated under the protection of the governors (voivodes) or the town landlords. In order to improve tax collection, in 1580 King Stefan Batory established so called Seym of the Four Lands (Waad arba aracot). At that time it had no counterparts in the whole of Europe. As a supreme body of the Jewish self-government, it fulfilled not only fiscal but also judiciary, legislative and opinion-leader functions.

Relatively favourable living conditions effected in the increase of the Jewish population. At the half of the 17th century in the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth there lived ca. 300 thousand followers of Judaism.

Lithuanian Jew with his wife and daughter, 18th century.

At first the Jews didn't differ from other burghers in their clothes. With the course of time however there formed specific type of Jewish outfit - black bekesha or chalat in case of the Hasidim.

|